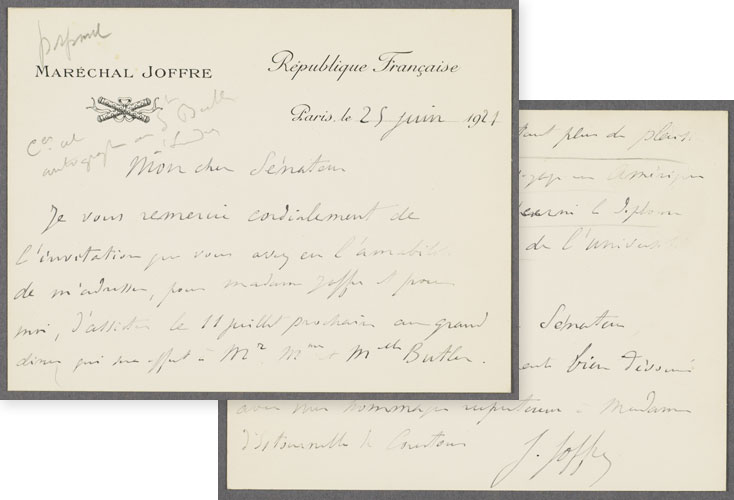

President Nicholas Murray Butler reading a message to Marshal Foch before conferring on him the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws, November 19, 1921

ICHOLAS MURRAY BUTLER, PRESIDENT OF COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY from 1902 to 1945, had deep ties to France and to Europe, and played a central role in the history of the Maison Française.

Butler attended Columbia College as an undergraduate, going on to earn his MA and PhD at Columbia (taking all three degrees between 1882 and 1884) and specializing in German philosophy. He next spent a formative year in Europe which, according to his memoirs, founded his “lifelong interest in international relations.” He studied in Berlin, and then at the Sorbonne in Paris, living on the Rue La Boëtie with a French couple, a high school teacher and his wife, who introduced Butler to their circle of scholars, writers, and artists.

Butler later decried the absence of foreign language studies in his early student days: “In fact, one of the great deficiencies of the Columbia College of that day was the utter lack of instruction in the European modern languages. Of French we heard absolutely nothing, and the same was true of Italian and of Spanish,” as well as German. Ambitious college graduates of his generation extended their studies in European universities, he wrote, because there were no “real universities” yet in the U.S. “To come under the influence of a European university was then the height of academic ambition. . . . After Berlin came Paris, and the American student who has missed that sequence has lost one of the great opportunities of the intellectual life.”

As he developed an educational philosophy and built Columbia from a college of 4,000 students into a great modern university with 34,000 students by 1945, Butler emphasized foreign—particularly European—language study and international scholarship as cornerstones of university education. The Maison Française was a building block in his internationalist strategy, as was the French visiting professorship that put Columbia, along with Harvard, at the forefront of university exchanges with France before World War I. Butler was closely involved in selecting the French scholars, including the first three: literary historian Gustave Lanson, philosopher Henri Bergson, and physicist Jean Perrin. Butler corresponded personally with Bergson, insisting that the philosopher stay at the president’s house rather than a hotel, and the two formed a lasting friendship.

Butler also called for more emphasis on spoken and written fluency in foreign language teaching—in lieu of a primary focus on reading literary texts—and supported early opportunities for Columbia students to travel and study abroad, including in France.

Butler had strong affiliations dating back to his student days with several European countries, particularly England and Germany, and he maintained these relations through annual summer travels to Europe. Among his German friends was Kaiser Wilhelm II, whom he visited several times in the early 1900s.

But it was with France and its leaders that Butler developed a deeply “intimate relationship,” starting with his 1885 stay in Paris. In his memoirs, he described himself in the third person: “As the young student moved about in the social and intellectual life of Paris and breathed the spirit of the place, he began to feel himself in companionship with the Greeks of modern times, the one truly civilized people in the world.”

Butler’s connections with French intellectuals and political figures grew during his summer sojourns to Europe. As he immodestly claimed, “I number among my acquaintances and friends almost every important man in France,” and these indeed included Aristide Briand and Henri Poincaré. He was often invited to deliver lectures and meet with dignitaries, and whenever Butler passed through Paris, fancy dinners and receptions with the Parisian elite were hosted in his honor and eagerly reported in French newspapers like Le Temps and Le Matin. Two of his close acquaintances, Gabriel Hanotaux and Paul Henri d’Estournelles de Constant (an influential senator, diplomat, and internationalist), were the cofounders of the Comité France-Amérique in Paris, and convinced Butler to become a found-ing trustee of the sister committee in New York. With d’Estournelles he created the Committee for the Defense of National Interests and International Conciliation and a European branch of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace based in Paris. Also, on a personal note, Butler’s second wife, Kate La Montagne, was half-French, and had spent part of her early life in France.

Although Butler’s European loyalties were divided, he clearly sided with France and against Germany during World War I, and by the war’s end, he had become a true celebrity in France. On a 1921 trip widely covered in the French press, Butler was received everywhere—at the National Assembly, the Académie Française, the Hôtel de Ville, the Cour de Cassation—and was ceremoniously awarded the Grand Officer of the Legion of Honor and celebrated in another round of dinners.

Butler’s support for France continued through the 1920s. The reconstruction projects he funded through the Carnegie Endowment included new libraries in Reims and Louvain (Belgium), for which he laid the cornerstones in 1921. He advocated for a revision of French war debts and promoted the 1928 Kellogg-Briand Pact, which renounced the use of war and called for the peaceful settlement of disputes. These efforts earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931.

In the 1930s Butler’s positions on European affairs were, at times, controversial. Like many American intellectuals, he was an early admirer of Benito Mussolini, whom he personally visited several times (Mussolini provided furnishings and some money for Columbia’s Casa Italiana, opened in 1927), only turning critical after the Italian dictator invaded Ethiopia in 1935. Butler held no such illusions about Hitler—though he did spark student protest in 1936 by sending a university representative to the 550th anniversary of the University of Heidelberg—and he took a vigorous stance against Fascism and for U.S. intervention in World War II.